Jammu and Kashmir

Jammu and Kashmir

Chronicling the Lived Experiences in a Conflict Zone: Dispatches from Jammu and Kashmir's Doda

It was late afternoon in mid-1996 when people began to arrive at our house to inquire about the health of my badi mummy (aunt), cousin, and brother. The whole conversation centred on the magnitude and effect of a bomb detonation in a neighbouring arcade, where three of my family members were caught up.

This was the year when state assembly elections in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) were to be held for the first time since the state's armed violence began in 1989.

Terrorists have attempted to sabotage the democratic process by targeting public places and intimidating civilians.

Badi mummy was severely injured, yet she miraculously survived. The cobbler she had employed to mend her shoes was not so fortunate and died on the spot. Everyone who came to our residence was told about how Cobler’s whole intestine had spilled over my badi mummy’s feet.

Militancy and I were born together: normalising encounters, IED’s, ambushes, and deaths.

This was nothing out of the ordinary for a seven-year-old. This was my normal for the entirety of my life, as I was born in 1989, when violent armed militancy had erupted in the state.

As a consequence, making sense of the surrounding environment also included always remaining close to home, differentiating between different types of gunshots (training, encounters, etc.) and explosions, and knowing where the rifle would be kept in the event of an emergency.

We were repeatedly warned not to enter forbidden forests or take a stroll on the cursed paths. We were warned that these forests and paths were home to child-eating monsters. Our games would mostly include army/police versus militants, among other themes.

Using words like "gunshots," "encounters," "IED ambushes," and "casualties" became normal in conversations from dinner time to the playground.

The school has been shut today!

The school was routinely closed due to violence. We waited for an announcement that the school would be closed the next day after any gunfire or bomb explosions.

The gullible younger self would not be concerned about the loss of innocent lives but would instead anticipate the declaration of a holiday (not a shutdown).

Only in subsequent higher classes did I realise that the frequent shutdowns were having a negative influence on education. Furthermore, as one begins to make sense of the world, losing individuals around you has a negative impact on one's mental health.

My closest friend's father, our neighbor, Bitu uncle, was assassinated in an ambush by terrorists in 2006. I was sleep deprived for days and couldn't stop thinking about Bitu Uncle.

My best friend tragically lost her mother in a road accident less than a year after her father died, leaving her with three younger siblings. She eventually had to drop out of school. The violence had uprooted her entire life, and as a woman, she had to bear it even more harshly.

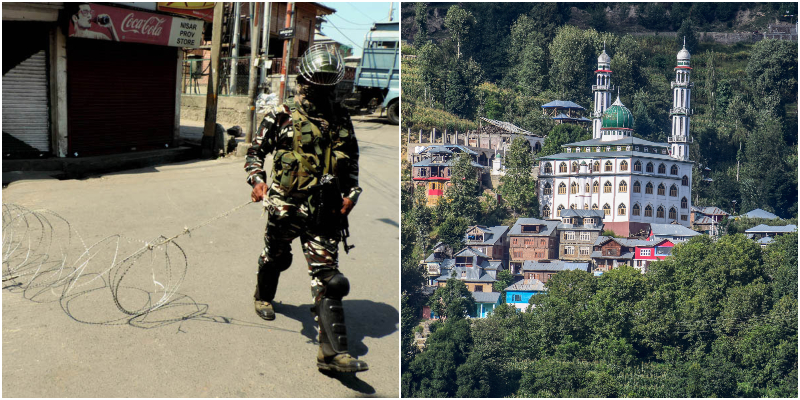

File image of Doda city in J&K by Arun Singh Suryavanshi via Wikimedia Commons

File image of Doda city in J&K by Arun Singh Suryavanshi via Wikimedia Commons

LTMs, PTMs, and FTMs

The Doda district, like other regions of the state, was at the epicentre of global Jihadism.

The fall of the Soviet Union and its withdrawal from Afghanistan has left militarily trained, ideologically driven mujahideens looking for a new cause.

The Pakistani state then redirected many mujahideens to Jammu and Kashmir.

The former also indoctrinated, sponsored, trained, and provided logistics to discontented youths in the region.

J&K was inundated with terrorist organisations that were generically categorised as Locally Trained Militants (LTMs), Pakistan Trained Militants (PTMs), and Foreign Trained Militants (FTMs). Among others, al-Jihad was the most active terrorist organisation in the Chenab Valley.

There were passing references to the presence of terrorists of foreign origins on various mountain peaks and forest ranges. After specialising on the same subject a decade later, it made sense to me how Pakistan exploited transnational Jihadist ideology to settle its account with its stronger neighbour.

The ideology was used as a way to frame the influx of Jihadis and to manufacture, radicalise and militarise local discontent.

"Us versus Them"

The militants also sought to exploit the communal rift by targeting the region's non-Muslim population.

Between 1996 and 2006, there were a number of mass executions in the region. Among these, the Chapnari massacre (1998) and the Kulhand massacre (2006) were extensively discussed; survivor reports included terrifying details about how the killing was carried out.

During these times, one had to identify with either sides, and the divisions of Us versus Them were commonly invoked. The feeling of unease also persisted in school for a while, although it vanished after a few days.

Posing a military challenge was inadequate for terrorist organisations and their patrons to consolidate their domination.

Their bigger objective included the imposition of ideology within society to give them acceptance and legitimacy. This ideological imposition was visible in people's clothing, which we (the younger generation) were told was alien to the region prior to 1989.

The militancy in the district has decreased over the last decade. Others may see the district's militancy as a statistical assessment, but for us (particularly the younger generation), the lived experience has had a seismic influence on our lives in the past, present, and future.

The 1996 bombing, the children-eating monster, Bitu Uncle, the Chapnari massacre, and the Kulhand massacre will live in infamy.

The author, Ekta Manhas, is a PhD from Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi.

Support Our Journalism

We cannot do without you.. your contribution supports unbiased journalism

IBNS is not driven by any ism- not wokeism, not racism, not skewed secularism, not hyper right-wing or left liberal ideals, nor by any hardline religious beliefs or hyper nationalism. We want to serve you good old objective news, as they are. We do not judge or preach. We let people decide for themselves. We only try to present factual and well-sourced news.